There is both beauty and necessity in that other F-word – FAILURE – and a need to make it a part of our innovation conversation.

You’d have to have been living in a cave (with limited radio reception) not to have heard the phrase ‘innovation generation’ bandied about.

It’s true: we’re living in an ‘innovation era’, a bi-partisan supported ‘ideas boom’ time, with Malcolm Turnbull putting $1.1 billion on the table to increase our ideas capital.

But with any new invention, concept or idea – indeed any risk – comes failure. Are Australians willing to embrace that good F-word, or at the very least, ready not to fear it?

Australia’s sporting obsession is all about winning and losing. Now and then a coach or captain might reveal a reflection about learning from failure. However, overwhelmingly the focus is on the winning narrative.

We are a sports mad nation, but has it affected the way we consider loss and failure?

If we do hear about failure, it’s usually for maximum Twitter impact – an elite athlete falling off the wagon in spectacular fashion, at a bar, on a plane, or in a hotel lobby.

So why has failure got such a bad name in Australia? What are we worried about?

One of the ‘brand challenges’ failure faces comes from the very fact we seem to emphasise and celebrate its more able sibling – SUCCESS – in almost revered tones.

Have a look at a primary school sports carnival. No longer are there ribbons for first, second or third. Now every child receives something for being there. There are no failures anymore. Only winners. Are we helping young children (and ourselves) learn if we can’t talk about failure or feel comfortable about not winning?

“It has been said FAIL stands for First Attempt In Learning.”

I have done this in many careers – including as a solicitor, judge’s associate, business analyst, marketer and strategic adviser.

An interesting failure reflection from my Supreme Court days was the composition of juries during murder trials. In many cases, older jurors were considered favourable by both defence and prosecution teams.

They were seen to have “lived” their lives and were often perceived as more empathetic and realistic about the dice that life had rolled for them – a dice that had given people many successes but, equally, failures. Failures that were unwelcomed but nonetheless experiences that sharpened awareness of human fragility and decision making.

So when and where is failure OK in the broader Australian conversation? How do we ensure it is not tokenistic and takes root so we may learn and grow from its lessons?

It’s not easy, as we live in a paradoxical paradigm. On the one hand there are many things we are comfortable with that have in-built failure: white goods for instance seem to last a tenth of the time than our parents’ generation and we seem OK with that.

Against this “acceptable failed redundancy” – perhaps acceptable in part because of the perceived low cost – we have a work culture that for many does not accept or reward failure. And if it does, it does so in curious ways.

Take the higher education sector. Academics at universities gain promotion and recognition for being ‘best on field’; that is, pushing the boundaries of scientific knowledge at the lab bench. Research breakthrough requires a creative mind and a readiness to experiment and take risks that may or not succeed.

For students, results are still driven in that binary fashion of pass–fail and students nearing graduation fear not being successful in finding jobs or failing in interviews.

In the professional sector the question is whether the culture is set up to celebrate and reward failure. There are many organisational leaders who may talk the ‘fail fast, fail better’ language to encourage a culture of innovation, but actions speak louder than words.

We all know managers who would rather not change something that isn’t broken, who fear that a new way or process might not match the results of the status quo, despite those results being sub-optimal.

So how can we create work-places where failure can be considered a valid part of an organisation’s culture, and where staff can feel comfortable talking about failure and learning from its rich lessons?

Pennsylvania State Emeritus Professor of Engineering Jack Matson, who teaches a popular course on Failure 101, suggested that when searching for jobs, candidates should also include a list of failures, not just successes.

Joannes Haushofer, an associate professor at Princeton, did this recently and his CV of Failures went viral.

It begs the question: when seeking candidates, do organisations look for characteristics of curiosity, appetite for risk, history of and ability to learn from failure? Do companies offer opportunities within their organisational structure to ‘play safely and experiment’, to test new ideas knowing many will fail, with no fear of retribution or penalty?

Sir Ken Robinson, Chair of the UK Government’s report on creativity, has written and spoken widely on children and creativity.

He highlights research about how a child’s ability to be creative and think in divergent, creative ways drops significantly as they mature. He suggests one of the reasons for this is that a student understands there might be a penalty for suggesting something that might not be correct, that is, providing a creative, risky, improbable idea.

“So even at a young age we are deterring children from being creative, from trialling and learning from experimentation.”

We are attempting to make them ‘fail safe’, contemporaneously limiting the learning that can come from these experiences.

Mindset is a good place to conclude this consideration of the good F-word for only by considering failure as a tool to learn from rather than the end game can we extract greater value from its lessons.

Stanford University’s Professor Carol Dweck’s work reinforces this. Her research suggests that it is not what you are born with that matters (i.e. whether you are born smart or not) but your mindset.

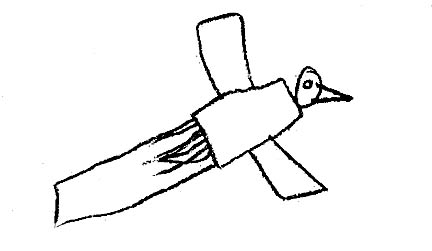

Above is a child’s bird drawn from experience and memory

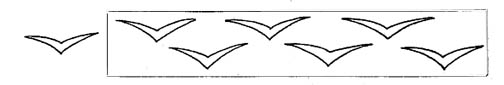

The child is asked to colour workbook birds for math (above)

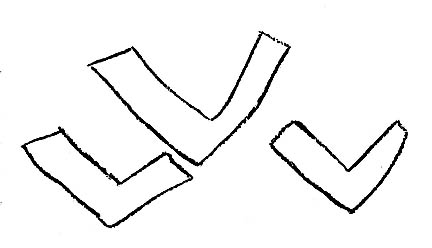

Birds drawn by this child after the stereotyping effects of the workbook

Illustrations: Viktor Lowenfeld, W. Lambert Brittain, Creative and Mental Growth, 1970, sixth edition

In a fixed mindset, she suggests people believe their intelligence or talent is set and success comes directly from these traits.

Consequently they focus on proving and demonstrating their talent rather than developing it. Failure is very difficult to reconcile as it jars with their fixed mindset of born, innate ability.

With a growth mindset, people believe their ability, talent, skills and achievements can be developed and demonstrated through effort, commitment and hard work.

They believe that what you’re born with is just the foundation, the starting baseline. Accordingly, having a growth mindset means one can enjoy the lessons that comes from experience even when things don’t go to plan. Failure is just that first attempt in learning.

For Australia to be comfortable with the F-word, we need to collectively embrace the growth mindset and allow failure to be part of the innovation conversation. An innovation nation demands this, for only then will the ideas boom really come to life.

This article was written by Jacyl Shaw, originally published in ‘Pursuit’, The University of Melbourne